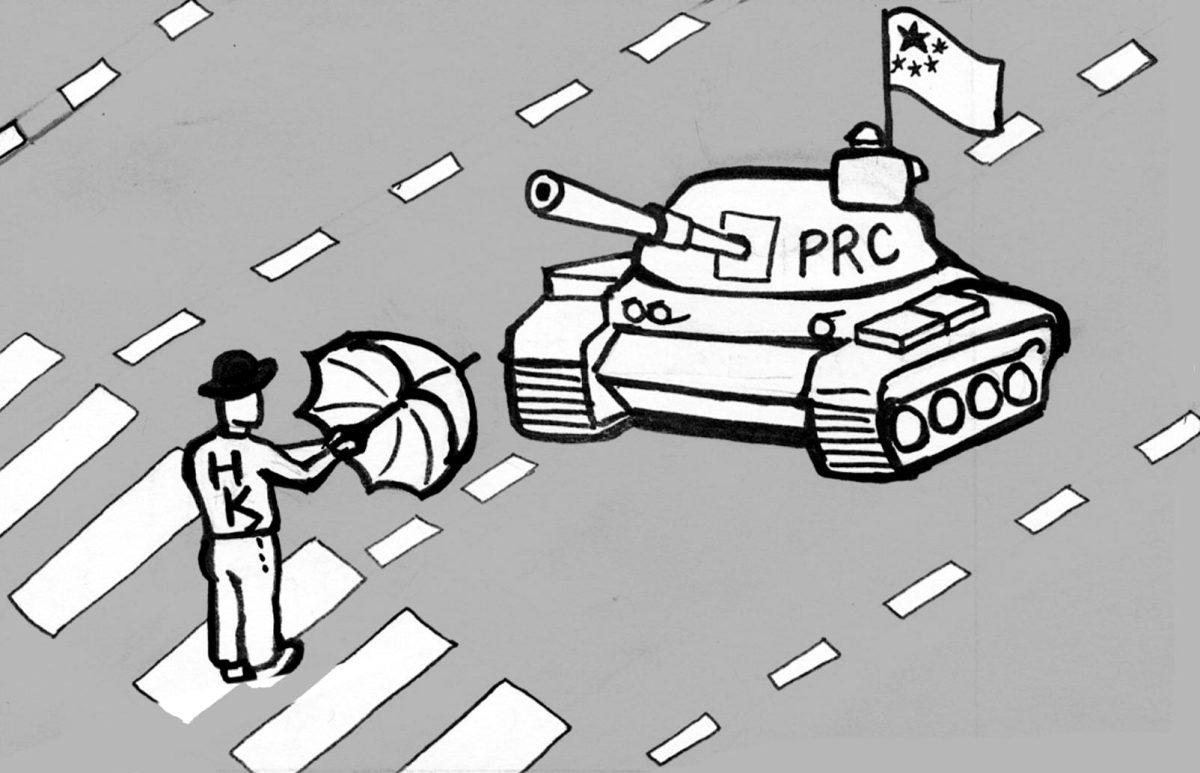

Earlier this month, the people of Hong Kong began an occupation of the city’s central business hub called “Occupy Central with Peace and Love.” As its title suggests, the movement has been peaceful, though many are worried that it could abruptly turn violent. Tensions are already mounting; the protests have been nicknamed “The Umbrella Revolution,” as participants have used umbrellas to shield themselves from tear gas and pepper spray used by the police.

The protests stem from a proposal written by the National People’s Congress that would limit democratic reform in Hong Kong. In 2007, it was promised that by the 2017 elections there would be a more democratic selection process of chief executive. Under today’s system, an election committee chooses the chief executive with no public forum. The 2007 promise outlined that in 2017, the election committee would choose three candidates that the population could then vote on.

The situation has drawn many comparisons to the 1989 protests in Tiananmen square. This is understandable, considering that the Umbrella Revolution is the largest pro-democratic reform movement in China since Tiananmen, but a direct comparison both instills fear and is somewhat inaccurate.

Hong Kong and Beijing are vastly different. Hong Kong operates under a separate set of laws, called Basic Law, that was drafted in 1997 when Hong Kong rejoined the sovereignty of China. The laws include freedom of speech, assembly, press and religion. The arrangement is called “One Country, Two Systems” and grants the city of Hong Kong more liberty than its surrounding nation. This setup has allowed a laissez-faire economic system to launch Hong Kong into economic prosperity.

As the capital of China, Beijing remains both an economic and governmental power. It lacks all of the aforementioned rights of Hong Kong and the legitimacy of the Chinese government is very closely tied with the operations of Beijing. The Tiananmen Square Protests of 1989 – when student leaders were forcibly suppressed by hardline leaders who ordered the military to enforce martial law in the country’s capital – was a huge embarrassment for the Chinese government. It came during an important summit with Russian President Mikhail Gorbachev. For a restrictive, puppet-like government in a country rich in cultural heritage, the reaction to the Tiananmen square protests was surprising, but also not exactly incomprehensible.

It’s important to note the change in China’s world presence from 1989 to now. During this time, China experienced a period of rapid economic growth, moving from the world’s eighth largest economy to the second. China made its grand entrance onto the world stage with the 2008 Beijing Olympics. Other countries became dependent on China’s labor force and manufacturing industry. But China’s rapid growth was never before seen, and it was accompanied with a severe wealth gap and overpopulation issue. China is very aware of its presence on the world stage today, and it is naive to say that the government would be so hasty as to replay Tiananmen in an area where the law grants citizens the right to protest.

Two former Chinese political prisoners, Yang Jianli and Teng Biao, have pleaded through an article in the Wall Street Journal to the United States and the world to prevent Tiananmen from ever happening again. The two ask the Obama administration to put pressure on the Chinese government to allow democratic elections in Hong Kong and also to “forcefully condemn” any violence against the protesters.

I agree that preventing another massacre goes without saying – however, there is yet to be one. We don’t want to take any preemptive action when the Chinese government itself is still deciding how to handle the situation. Also, it’s important that we choose our battles wisely. With a country as influential as China, meddling in local demonstrations will do more harm than good. As the former political prisoners noted in their article, the world is – and will continue to be – on watch.

Emma Whitford ’18 [email protected] is from Middleton, Wis. She majors in political science.

Graphic Credit: ERIN KNADLER/MANITOU MESSENGER