Recently, Minneapolis schools have been embroiled in a conflict surrounding school suspensions for students. The issue has ignited debate about race and suspensions.

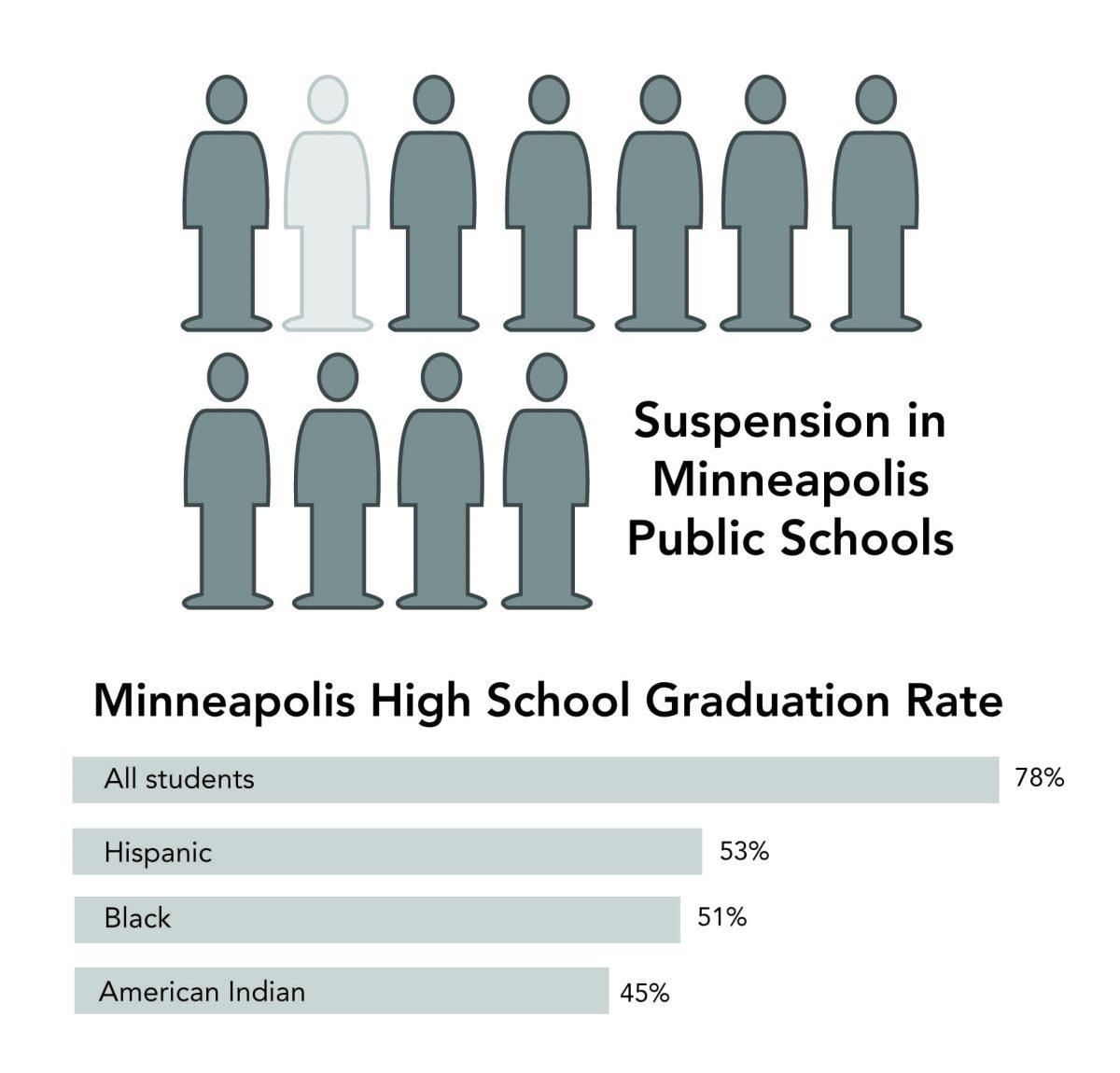

Minneapolis Superintendent Bernadela Jones is changing the suspension policy in Minneapolis public schools to combat the unfair treatment of minority students. New data reveals that black students are 10 times more likely to be suspended from schools than white students, reflecting some problems that the superintendent and other school officials hope to address by approving all suspensions excluding cases of violence before the student is sent home. The superintendent’s hope is to eliminate the racial gap in suspensions by 2018, while closing the achievement gap by 2020.

The U.S. Department of Education’s graduation rates show that Minnesota – as of 2012 – has a high school graduation rate of 78 percent. The break down according to race is disproportionate. Racially black students have a graduation rate of 51 percent, and Hispanic students have a rate of 53 percent. The group that suffered the most were American Indians, who graduate at a rate of 45 percent.

There are many contributing factors that influence the graduation rate, such as district funding, access to a school, student-to-teacher ratio and family involvement. Minneapolis schools are now saying that suspension rates are also a factor.

According to statistics cited by Superintendent Jones, racially black students are also even more likely than their white peers to be sent home for the same offense. Jones is asking for future nonviolent suspensions cases of students of color to be reviewed by public school officials.

There has been pushback on this new policy by teachers who think they now have to accommodate students who are being disruptive to the learning environment. Many teachers are claiming that this disruptive behavior is a result of untreated mental illnesses or behavioral issues.

These responses to the new policy are cop-outs. There is strong evidence to support a disturbingly large graduation gap, but also that suspension rates may factor into that outcome. Also, by attributing the behavior to what they perceive as “mental illness” or “behavioral problems” is to ignore one thing: race.

By ignoring race and not reflecting upon internalized racism and prejudice, it is easy for teachers who are racially white to justify their suspensions by simply saying that “this is just how this group of students acts.” If this is “just how students act” then the suspension rates would not point to an inordinate gap between white students and students of color. Racial profiling is not a new thing, nor a thing that has gone out of style.

In other words, teachers have internalized negative stereotypes and generalizations about people of color and let these stereotypes infiltrate the classroom.

Many would say that this is discriminatory to the white students, but as stated in a recent Star Tribune article, they aren’t being suspended for the same behavior as their racially diverse peers. Certain privileges are being extended to racially white students by their teachers and school officials.

Suspension policy has two purposes: to stop students from disrupting the learning environment and to discourage poor behavior. Although removing a student may create a peaceful classroom environment, it does nothing to rehabilitate the student. Suspension removes the “problem” from the classroom without fixing or addressing that “problem.” There are even plans to reduce police forces, as many are saying these suspension rates are also a factor in the school-to-prison pipeline that has been created.

In reality, though many would like to think that making someone “pay time for their crime” changes behavior, it has shown time and time again to be ineffective. There are greater structural problems that need to be addressed.

Removing a student from the classroom for any amount of time means that the student is accumulating large quantities of homework without the instruction to understand the material. This student now not only has a record with the school but also poor grades. If the student is not receiving passing grades they will be failed and held back. By missing out on the credits, they either do not graduate on time or at all. Because these students tend to be students of color, it perpetuates the cycle of poverty.

There are other ways of addressing the suspension gap and graduation gap at the same time. For instance, implementing adequate training for teachers to teach in a multiracial and cultural environment might foster a sense of interracial acceptance. Having teachers understand the environment that they come from contextualizes students’ experiences and leads to understanding. It also addresses internalized racism that could lead to racially-charged suspensions.

Another tactic that should go into effect is increasing the percentage of teachers of color relative to students of color. According to an article from Minnesota Public Radio, 30 percent of students attending public schools in Minnesota are students of color. Yet the percentage of teachers of color is around three and a half percent, hovering below the national average.

Suspensions are causing more harm than good for our students of color in Minnesota. This new policy and possible additional routes of implementing change will close gaps in suspension and graduation, and will help public schools become a place of equality for all children.

Cynthia J. Zapata ’16 [email protected] is from Rosemount, Minn. She majors in English and race and ethnic studies.

Graphic Credit: ERIN KNADLER/MANITOU MESSENGER