In Jan. 1922, an unnamed St. Olaf student writing for the Olaf Messenger — then the Manitou Messenger — decided that “now that the prudish conventions which previously limited women to the home have vanished as completely as the popularity of lavender and old lace, or grandmother’s hoop-skirts, and women are permitted to pour forth their energies in any field, men can no longer be compared man to man but man to woman.” The article, titled “Co-ed Initiative No Longer Bound By Hoop Skirt Conventions,” goes on to proclaim: “True to type we find that the men favor mathematics, economics, and history, and that the women prefer the education and music courses. Twentieth century equality seems to have lessened the proverbial ‘squeamishness’ of women, for the biology classes boast a large majority of coeds, and even the philosophy and sociology courses contain a generous number of representatives.”

However much this “twentieth century equality” appeared to dissipate gender conventions, it is obvious that true equality had not been reached in 1922.

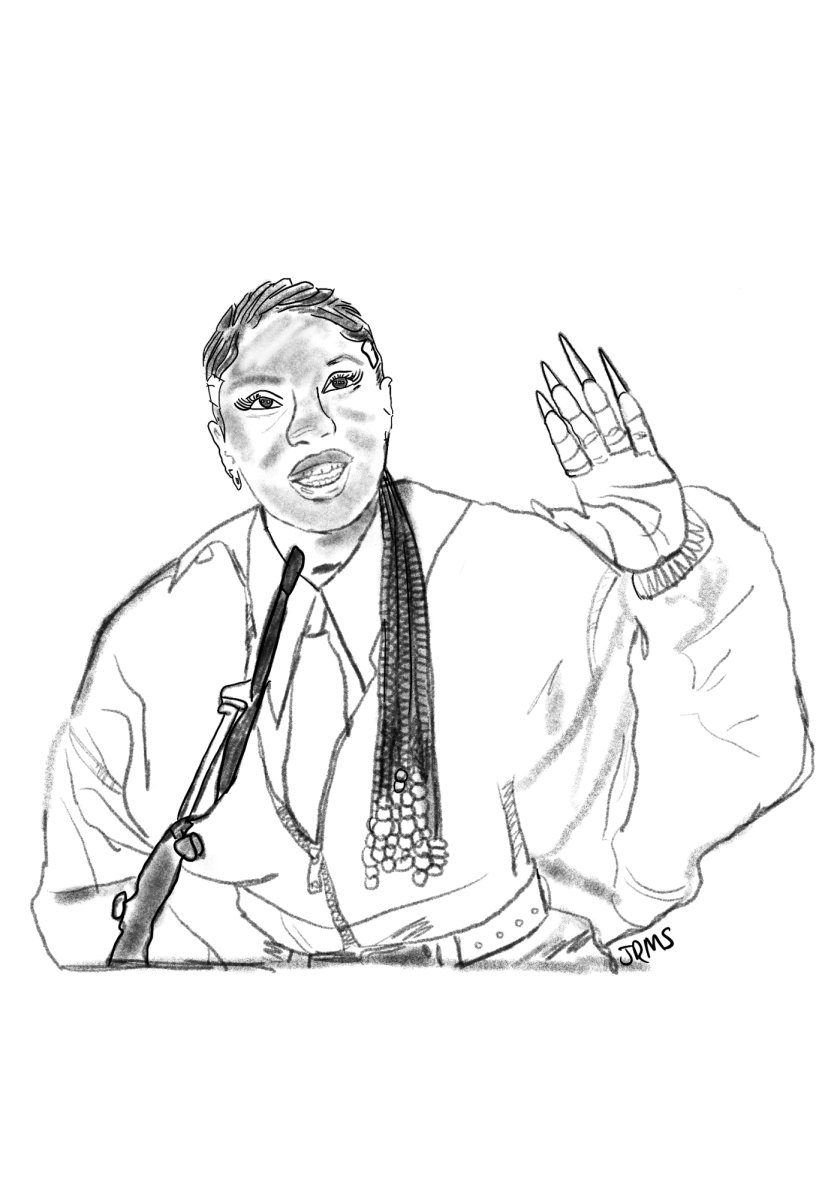

In Sept. 1975, Kathy Holmes ’76 wrote a piece titled “Not Joan of Arc, but she’ll do” featuring an interview with the newly hired women’s studies coordinator, Gretchen Kreuter, professor of history. St. Olaf did not yet have a women’s studies major, but the curriculum was beginning to include courses focusing on women’s history and literature. Holmes described challenges that St. Olaf, and academia across the country, continue to face: “The lengthiest and most tedious job will be the restructuring of courses that don’t represent women justly. Kreuter suggested a way of testing a course in its treatment of women, ‘When you’re taking a class and someone talks about humanity, ask: Am I included? A liberal arts course that leaves out half of humanity isn’t really liberal.’” Kreuter’s concern about just representation in our courses persists today — especially in programs like the Great Conversation, where white, male voices continue to dominate discussions.

It would not be until 1984 that the St. Olaf faculty would vote to add the women’s studies major to the St. Olaf curriculum. Frances Schwartzkopff ’84 offered a critical opinion in their 1984 article introducing the major, “Women’s studies: major development?.” Schwartzkopff wrote that the addition of the major, while a positive, “is insufficient if the faculty wishes to include feminist analysis in the liberal arts education. Realistically, the major will not attract the number of students that biology or English do. And of those students who become Women’s Studies majors, most will be women. Consequently, the majority of students will never hear of, much less study, feminist analysis.” Schwartzkopff, like Kreuter, contended for St. Olaf’s need for the integration of feminist study and women’s voices into all disciplines. Both realized the need for just representation of women in all aspects of the liberal arts education — a need that has not yet been fulfilled.

Today, the women’s studies major no longer exists: instead, the women’s and gender studies major explores the intersectionality of gender, race, class, sexual orientation, nationality, ability, religion and age, across many histories and cultures. Women’s studies are inextricably tied with other vital disciplines such as race and environmental studies. Now, we fight for the just representation of LGBTQ+ and BIPOC voices, always striving towards some kind of equality. Majors such as women’s and gender studies and race and ethnic studies are important — but the integration of LGBTQ+, BIPOC and female voices into a wider array of courses is equally vital.

In 1922, hoop skirts no longer confining female students, a student decided that we were there: we had found equality. Kreuter and Schwartzkopff recognized that the battle for equality is ongoing: from Joan of Arc to today, we keep fighting.