By Jacob Maranda & Claire Strother

Executive Editor & Features Editor

“St. Olaf’s School,” the advertisement read. “Northfield, Minnesota. Two Courses of Study. Six Teachers.”

The first edition of the Manitou Messenger in 1887 featured two advertisements: one for a host of restaurants, dry goods and stationery stores, and the other for an upstart Lutheran institution in southern Minnesota out of which the Messenger ran.

Alongside these ads were a valedictory address, a piece detailing the new school orchestra and an article explaining the name of the school’s first and oldest student news publication.

“The Indian is gone,” the final article read, “but the Great Manitou still exerts some of his power of long ago in legend and tradition, a presence not ignoble because evolved from the consciousness of a savage race.”

Made clear in this one line, the founders of St. Olaf College, then St. Olaf’s School, were not only cognizant of their complicity in colonialism, but took great pride in it. The final line of the article reasserts this.

“‘Forward, forward, soldiers of Christ, soldiers of the Cross, soldiers of the King.’ A message pointing to a service of God and one’s country, faithful unflinching, no flourish of past achievements, no flutter of past laurels, but a work on and on, a progress as relentless as the march of Time himself.”

Racist connotations permeate the nature of these justifications, which are ignorant of the histories and lives of the people that the College’s founders originally uprooted. In this sense, mere acknowledgement is not enough to grant justice to these first inhabitants. Justice requires a definite change to turn away from this publication’s problematic history.

With this in mind, the current staff is proud to rename St. Olaf’s first and only student news publication to The Olaf Messenger.

Continue reading for more Native American history at St. Olaf throughout the College’s 146 years of standing.

Manitou Hill

“Before us was spread a most beautiful panorama as far as the eye could reach,” wrote L.S. Reque, one of the two original professors at the College, in a letter to the Messenger in 1914, St. Olaf’s 40-year anniversary. “‘How will this do for a college site?’ asked Harald. I said, I did not think he could find any better. We went home and became busy talking Manitou Hill. And there stands St. Olaf College now.”

Reque, alongside Professor Thorbjorn N. Mohn, consistently referred to this location in his letter, alternating between the names of “Manitou Hill” and “Manitou Heights.”

Both of these titles derive their names from an aboriginal spirit, the Manitou, found in Algonquin languages spoken by various Native American tribes. Native peoples use the term Manitou to refer to a “Great Spirit” that animates all living beings.

The name is part of the vocabulary of the Ojibwe tribe, whose traditional territory extended through parts of northern Michigan, Wisconsin and Minnesota and into Canada. This territory bordered that of the Dakota tribe, located in what is now southern Minnesota. It is unclear whether the Dakota people used the term in their own vocabulary, although many scholars see a close connection between the Ojibwe and Dakota tribes that often traded and fought in north and central Minnesota.

It is difficult to track where the name “Manitou Hill” first originated. It may be that the Dakota people granted that name to the hill, and the Norwegian immigrants simply assimilated the term. It may be the other way around, in which Norwegian immigrants named the hill in a sort of homage to the Native inhabitants.

In a brief piece from volume 67 of the paper, which was published in 1954, the Messenger offered its own explanation.

“‘Manitou’ doesn’t mean ‘steep,’” the article reads. “And ‘Manitou Heights’ are so called, because local Indians found them mystic and strange; a possible home of the gods.”

It continues, “‘Manitou Heights’ attracted and awed the pioneers of this area and the name remains.”

Whatever story may be true, the name stuck and is present around campus to this day. Examples include the former title of this publication; the Manitou Singers, the College’s treble voice first-year choir; and Klein Field at Manitou — often just called Manitou Field — where St. Olaf’s football team plays.

Native Americans at St. Olaf

As recorded in the fall 2020 student census, one American Indian or Alaskan Native student is currently enrolled at St. Olaf. In 2019 there were zero.

For a school that employs Native names in its buildings, organizations and practices, the disconnect between the College and Native American students is apparent. The school’s history provides further evidence of this rift.

St. Olaf became actively involved in Native American recruitment after former Professor of Sociology Ken Olsen wrote the “Proposal For a Program of Education For American Indians at St. Olaf College” in 1970. In response to this proposal, St. Olaf hired Phil Allen, a Dakota Native, as a recruiter and director for the newfound program the following year.

“For the academic year 1972-1973, as a result of Phil Allen’s recruiting efforts, 18 Indian students were enrolled at St. Olaf,” Christopher Hagen ’80 reported in the Messenger in 1979. “Prior to this time, only a few people with Indian heritage came to St. Olaf. By the fall of 1974, most of the Indians at St. Olaf had quit.”

In 1976, Lawrence “Larry” Martin, a Native American social work scholar and activist, arrived as the coordinator of Native American affairs at St. Olaf. As part of a continued push by the College to recruit Native American students to campus, Dr. Martin hosted various seminars focused on Native American culture and taught an interim course titled “Native American and Religious Principles.”

Martin also led a new Native American Students Program on campus. St. Olaf founded the program after a group of students and non-students presented a “Preliminary Statement on Native American Concerns and Consciousness within a St. Olaf Environment” to the administration in 1975.

“It sought to prompt discussion on Native American student life and support, Native American studies and Native American sensitivity and values,” Hagen reported in the Messenger in 1979.

After three years, the College cut the program and dismissed Martin as its director. An article published in October 1979 explains the decision.

“In trying to define the reason more precisely, Larry Martin was told he had not done an ‘adequate’ job,” the article reads. “When presented with a review of projects and other facts (which included a summary of admission activities), President Rand agreed that Mr. Martin had done his work satisfactorily. St. Olaf has reassured interested people that it still has a genuine interest in Native American presence at this college. Yet, Mr. Martin still won’t have a position on this administration and the Native American program is still being dismantled.”

The foundation of the Native American Students Program came during a period in the late 1970s when St. Olaf appeared highly interested in its enrollment of minority students. Paul Svoboda ’81 covered the issue extensively in the Messenger.

In 1977, St. Olaf formed the Race Relations Committee. The group was tasked with increasing minority enrollment at the College, specifically for Black students. Part of their goal was the hiring of a full-time Black admissions counselor, who would be tasked with recruiting Black students to the College. Previous recruitment of Black students in 1973 prompted this recommendation.

“The College made a similar effort that year to increase its Native American enrollment and hired a counselor to recruit students from various Indian reservations,” Svoboda wrote in an article from 1979. “Nineteen Native Americans came to St. Olaf in 1973, though most left by the end of the year.”

St. Olaf’s efforts to increase minority enrollment proved largely unsuccessful, as reported by Svoboda in the same article.

“Five years ago, St. Olaf’s enrollment included 65 blacks and 19 Native American students,” Svoboda wrote. “Since then the College’s minority population has decreased substantially; today there are only 20 blacks and three Indians attending St. Olaf.”

Many around the College felt this drastic decline in minority enrollment was a serious cause of concern.

“There is little doubt that the minority enrollment situation has reached a crisis,” an editorial from 1979 read. “The Regents always welcome student input, and we think we speak for the vast majority of students when we say that there needs to be more action taken on minority enrollment.”

Following these efforts in the 1970s, St. Olaf has focused little administrative attention on the recruitment of Native Americans to the College. Activities involving Native Americans on campus have primarily revolved around awareness weeks or specific cultural events.

Efforts for acknowledgement

In November 2019, former Student Government Association (SGA) President Devon Nielsen ’20 introduced a land acknowledgement resolution to the student Senate. This resolution, a core part of Nielsen and former Vice President Ariel Mota Alves’s ’20 campaign for SGA executives, highlighted ongoing conversations between the executives and other parties, including Vice President for Equity and Inclusion Bruce King and Northfield city government.

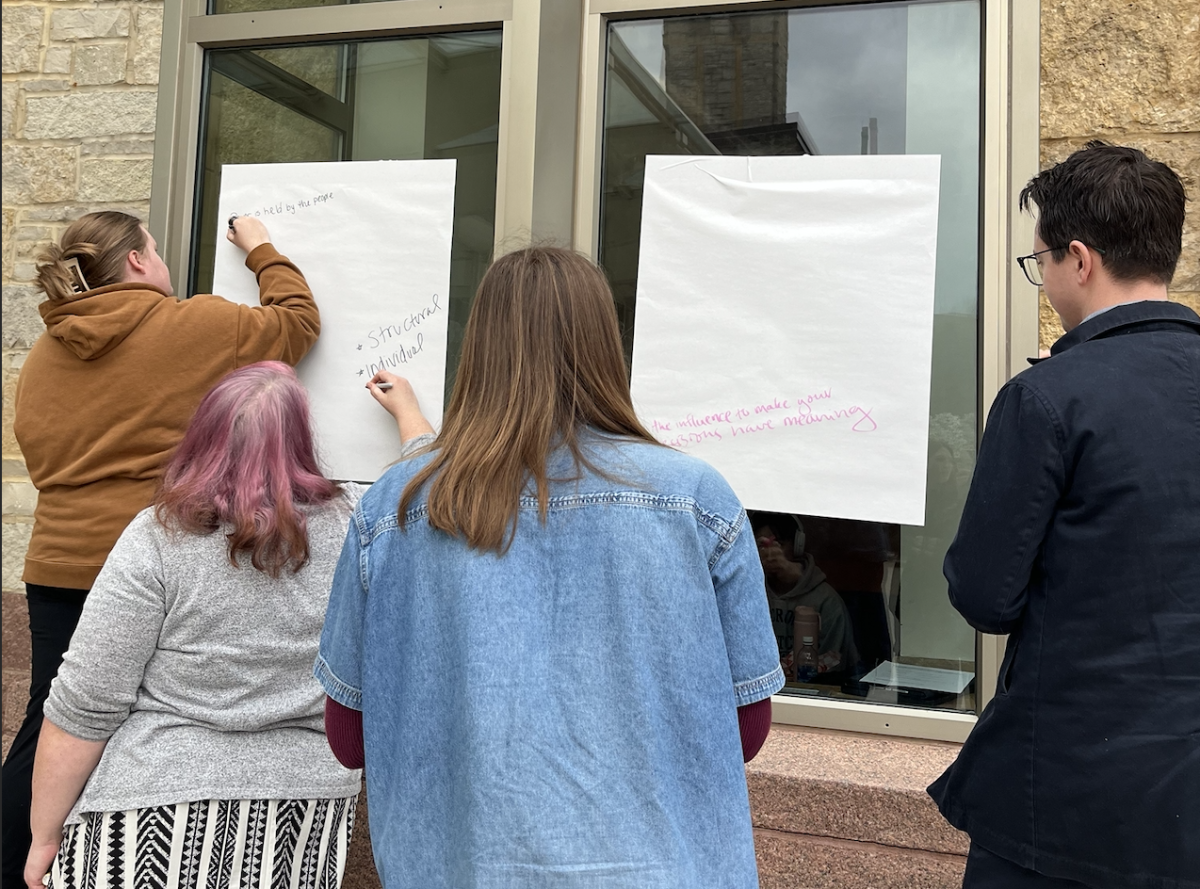

At the Nov. 5 Senate meeting, Nielsen described the land acknowledgement resolution as a “stepping stone to discuss more constructive ways in which St. Olaf can address injustices faced by Indigenous communities.” The resolution passed a Senate vote in April 2020.

Current SGA President Melie Ekunno ’21 sees the mere acknowledgement of the land’s origin as an empty gesture and calls for more reified change during her tenure.

“Unless you have spent your life in denial about racism, and in denial about historic injustice, then saying ‘I acknowledge my privilege’ is nonsense,” Ekunno said. “There’s no question of the fact that this exists and this happened. So it is not enough to say that we acknowledge that we took this land unjustly from people.”